Humboldthain Flak Tower – Project

History

The flak towers (flak = anti-aircraft guns) were once the largest bunkers in Berlin. Measuring about 23 by 50 metres (control towers) and about 70 by 70 metres (gun towers), they loomed monstrously over their surroundings with heights of up to 42 metres. From October 1940 to April 1942, a pair of flak towers, consisting of a control tower and a gun tower, was built in Tiergarten and in Volksparks (people’s parks) Friedrichshain and Humboldthain. The flak towers in Volkspark Humboldthain were built between October 1941 and April 1942.

The short construction time of six months per pair of towers was only possible through the use of up to about 3,200 workers, including foreign workers, conscripts, and prisoners of war, as well as through 24-hour shift work and top priority classification of the buildings as important to the war effort.

While the control towers used their optical and radio equipment to locate Allied aircraft and determine their course, altitude, and speed, the gun towers fired four heavy, double-barrelled guns of 12.8-centimetre calibre to prevent them from flying over the city centre. Light flak on both towers served to defend against possible low-flying attacks. The military success of the flak towers ultimately fell far short of expectations, but they also provided shelter for thousands of civilians over six floors (officially approx. 15,000 per gun tower, 7,500 per control tower). With walls up to 2.5 metres thick and 3.8-metre-thick ceilings, these bunkers were considered absolutely bombproof. In addition to military accommodation and functional rooms, they housed air force hospitals and armament research centres, or served as shelters for works of art from Berlin museums. After brief post-war use, the flak towers were blown up by the Allies and their remains completely demolished (Zoo bunker) or buried under mountains of rubble (Friedrichshain, Humboldthain).

After years of work, we have made the interior of the ruins of the Humboldthain gun tower accessible to visitors; it has been open to the public since April 2004. You can read more on the work put into making the ruins accessible under “Restoration”.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Grünflächenamt Wedding

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

Eyewitness reports

In addition to their military function, the flak towers also served as shelters for the civilian population.

We have summarised some of the memories of those seeking shelter, as well as those of the young air force helpers who increasingly took the places of the anti-aircraft soldiers from 1943 on. Some of them come from a series of publications on the “Bunker Berg” exhibition by the Heimatmuseum Wedding from 1995/96.

Collected reports of civilians seeking shelter

(Ms Sch.)

“Sometimes, you had the impression that the bunker was collapsing because so many people were coming, with hand carts on which they had their belongings...”

(Ms O.)

“There was a large entrance, where cars could also enter, and where the ambulance came to pick me up after the delivery. There was also the lift. The room where I gave birth was right next to the lift.”

(Mr Ba.)

“Ten bombs fell on the bunker one Sunday. It shook like a duck’s ass. There were no banisters, so people flew down the stairs.”

(Ms Lb.)

“... There was no daylight in the bunker, and everything was closed when there was an alarm. The rooms I entered were only furnished with benches. Maybe 50 or 70 people could have fit in there.”

(Mr A.)

“Our neighbour had a room in the bunker. I looked at it and was horrified. Not the equipment, which was relatively minimal, this concrete building, it was sweating. I touched the walls and they were damp and slippery.”

(Mr D.)

“Thousands of civilians were in the bunker until the surrender. The military supplied them with rations using a sutler’s wagon.”

The eyewitness accounts are taken from the publication series on the “Bunker Berg” exhibition in the Heimatmuseum Wedding, 1995/96.

Migration to Humboldthain

A report by Bärbel Becker (*1939)

I was born in Berlin in August 1939 and lived at Stralsunder Strasse 43 at the time. I can remember that we went into the Humboldt bunker during bombing raids. It was like a mass migration; Mutti pushed the pram with my little sister and told me not to trip and fall, because then I would be trampled to death. Once we went a different way and I asked why. My mother just said, “We won’t make it to Humboldthain, we have to go to Bernauer Strasse to a small bunker.” I always had to put the clothes I took off in the evening neatly on top of each other on the chair because if there was an alarm, I had to get dressed fast. Once there was an alarm like that and we had to go down to the cellar very quickly. Then we all sat down there and listened. After a while, the walls started shaking and we got scared. Some of us said: “Now our house has collapsed!” Then, when it stayed quiet and the all-clear came, they carefully opened the door upstairs and realised: “Our house is standing. It was the neighbour’s house.” I can’t describe how everyone fell around each other’s necks and shouted, “We’re still alive!” Tears of joy were also shed. Then we somehow got out of Berlin to Silesia, to my grandparents, who owned a large estate with a confectionery shop, until the Russians came and we had to flee.

We thank Ms Becker for allowing us to reproduce her memories here.

Collected reports of the flak helpers

(Mr K., flak helper, born 1927)

“To mark that we were HJ (Hitler-Jugend = Hitler Youth), we always had a big swastika armband on our left sleeve, so that we couldn’t be mistaken for real soldiers under any circumstances.”

(Mr Sch., flak helper, born 1928)

“The training was very hard. It wasn’t even as hard in the Wehrmacht afterwards... At that time, the air force helper was basically the most defenceless rabbit in the hierarchy, and anyone who wasn’t an anti-militarist by then could become one.”

(Mr H., flak helper, born 1927)

“... or we had to go down two flights of stairs with the lockers in the spiral staircases and back up again. This senselessness was carried out in order to enforce discipline.”

(Mr Schw., flak helper)

“Flak was actually a pleasant break from school days, we just shirked Latin.”

(Mr H.)

“Then we were trained on the 2-cm flak gun, single gun and also quadruple. This kind of training was actually accepted without grumbling.”

(Mr Sch.)

“We learnt weaponry out of self-interest so that you could defend yourself, but you couldn’t defend yourself against fear.”

The eyewitness accounts are taken from the publication series on the “Bunker Berg” exhibition in the Heimatmuseum Wedding, 1995/96.

Luftwaffe helpers in 1944 in Berlin and near Leuna

A report by Dr Wolfgang Waldhauer (*1928)

This report includes some photos I took of the Humboldthain flak tower in February 1944 - in one of them, you can see a bit of Luftwaffe helper Chr. F.’s head. One Sunday, the two of us wandered carefully around the two towers and the rest of Humboldthain, picking up flak splinters and a half-burned stick bomb, careful not to miss greeting anyone, and then we forced ourselves back into the musty-smelling huge building where we lived on the top floor, together with the guys from the secondary school in our hometown. From time to time, Private v. S. looked after us and explained the bell signals “prelude” and “alarm” - indeed, it rang right on the first evening, on January 14th, 1944, after we had marched into the tower in civilian clothes in the afternoon and the guard had cheerfully called out to us: “You won’t be getting out of here any time soon!”

Very early in the morning of that day, we - about 20 boys born in 1928 - pupils at the “Robert Schumann School”, a humanistic grammar school in Zwickau/Sa, had gathered in the hall of the main railway station, some accompanied by their parents. A non-commissioned officer in the blue-grey uniform of the Luftwaffe with red collar patches met us there and we travelled in reserved compartments by train towards Berlin. When the train reached the suburbs of the “Reich capital”, we saw the first completely burnt-out rows of houses in Lankwitz, and the brash conversations in the compartment fell silent. Stepping out of Gesundbrunnen S-Bahn station, we then saw the huge concrete block of the “Humboldthain” flak tower in front of us - so that’s where we were going to live in future! At least we were “allowed” to take the lift to the top first, and there followed a cursory medical examination, outfitting (we were also given a tin identification badge like “real” soldiers!) and a briefing on the accommodation, which was equipped with double bunk beds and tin lockers.

The view from the man-high windows, which could be closed with a thick steel screen, looked out over the S-Bahn tracks onto the almost burnt-out façades of houses; only one house was still at least partially inhabited. The heavy night raids of November 1943 had caused this destruction as the schoolmates of the class of 1927, who had been on duty here since September 1943, told us. They greeted us with a mixture of pity and gloating: “So now it’s your turn too...!”

In front of the gun tower in Humboldthain - Berlin, February 1944. The turrets were painted grey-green and towered high above the old trees of the park, which had been damaged by bomb splinters in November 1943. On the surrounding balcony, the 2-cm anti-aircraft guns were mounted on concrete pedestals, on the upper platform, four double-barrel guns of 12.8-cm calibre.

I went on duty for the first time without a steel helmet because one of this considerable size had not been in stock, which initially resulted in a “scolding” and a remark about horses which, as is well known, have bigger heads... The non-commissioned officer who had picked us up from our home station soon turned out to be a teacher in disguise, and a second such person, a Westphalian, was then our instructor, together with Ogfr. R., a master painter from Hamburg, who looked sick to his stomach. “The 2-cm Flak 38 as such breaks down into...” It was the 2-cm Oerlikon Swiss precision product, and it became one of the few joys of my existence as a Luftwaffe helper to take it apart and put it back together properly! The base of this gun can still be seen today if you climb up the winding paths of the southern side of the Humboldthain gun tower, which was only half blown up and then filled with rubble, between trees and bushes to reach the level of the 12.8-cm platform. In one photo, Otto M. and Hans K. pose on such a cannon, of which there were also varieties with four barrels, the so-called “Vierlinge” (quadruplets).

Of course, the main aim of this “service” was to train us - as soon as possible - to become fully-fledged operators of these weapons, down in Humboldthain in a small sports field. However, “infantry service” also took place regularly and, in the beginning, we often practised standing at attention and saluting, although the Hitler Youth should already have “pre-trained” us sufficiently in this respect! Weapon service was much more popular, especially as it allowed us to demonstrate our own technical understanding.

Most of the time, the tone of the superiors was not excessively harsh - we already knew the usual yelling during drills and “infantry duty” in front of the tower from the Hitler Youth service, and even the intensified drills and push-ups practised here were mostly accepted as the unavoidable hardship of military training. Luftwaffe helper Hans K., however, still remembers with bitterness the evening of punitive actions a non-commissioned officer called a “masked ball”, for which we had been given some reason and that, for a similarly trivial reason, the battery commander D. “made the whole battery happy” with several hours of infantry duty...

It was not only on such occasions that we, some of us not even 16 years old, looked forward to the next short leave, which was to be granted to the Luftwaffe helpers about once a month, provided that there were enough gun crews left to fight. Short leave consisted of two days of leave and two days of travel, so that by making a clever selection from the Reichsbahn timetable - we were also allowed to use Wehrmacht holiday trains - it was quite possible to squeeze out more than 48 hours of “home time”. On Tuesday morning at the start of duty, however, you had to report back to the tower without fail! Once a year, there would even be a 12 plus 2-day home leave - but for us beginners that was still a long way off...

Mostly, during meals in the mess hall, we also met Luftwaffe helpers from Berlin schools who, however, mainly did their duty on the large 12.8-cm double barrel guns on the upper platform. Because of this and their frequent night missions, they looked down on us Saxons on the surrounding balconies with the light 2-cm weapons; several times some of them called us “you stubborn Saxons”, by which they probably meant that, compared to them, we were far too well-behaved and obedient in following all the regulations, while they took a much more relaxed view of the whole thing.

But many Saxons were not so well-behaved. In Berlin, we were accompanied by an equal number of students from the Zwickau secondary school, who then stayed in the same accommodation as us. We were astonished to find that their way of speaking was often peppered with unabashedly critical expressions of the regime and that they had a considerable fund of so-called “whisper jokes” (Flüsterwitze) at their disposal. Two of them also liked to play “Hitler and Mussolini meet at the Brenner”, one squatting on top of a double-decker bed, miming the Duce, with a Roman salute and chin raised threateningly forward, while in front of the bed, facing him, stood the other, holding a comb under his nose, with the other hand upward saluting the “Führer” with his arm bent back over his shoulder.

The “Battery Song”, which was more bellowed than sung when marching, began with “Hoch drooom, auf dem Beeerg, gleich unter den funkelnden Steeernen...” which was supposed to be a reference to our gun emplacement, about 35 metres above the ground; the “black-brown hazelnut”, a song we already had to sing in the Hitler Youth, also rang out between the damaged tree trunks of Humboldthain on its sports field, although the guy the song was about did not exactly correspond to the blond, blue-eyed ideal of the “Third Reich”.

After we had learned to “greet” properly, we were allowed to leave the tower compound for the first time, accompanied by two sergeants, and marched through some of the streets of the Gesundbrunnen district. The destruction that had already been wrought by the winter of 1943/44 was shocking, including stretches of side streets that had buckled and been torn up when a high-explosive bomb hit the sewage system. A large cinema on the corner, however, had remained intact, and we were once allowed to see the film “The White Dream” - the one with the song about the balloon: “... imagine it flies away with you...”, which then rhymed with “illusion”. Some of us would have liked to “fly away” even then - but nobody let on... And one Sunday we were taken to a nearby football field as spectators, where we were quite bored.

It was only at the beginning of March that our year group was ceremonially sworn in during a light snowstorm in a nearby park. We stood in a square around a 2-cm quadruple gun, which had been lowered from one of the towers with the help of the crane installed there and transported here for this purpose. Two Luftwaffe helpers had to put a hand on a barrel of the gun and all had to repeat a text which I have forgotten. I only remember that I was very cold, especially as we had probably marched there in “dress uniform” but without coats.

A supervising teacher from our school lived over in the control tower and taught the pupils of the class of 1927 on some mornings of the week. We 28s joined them after “basic training”; the whole troop hiked over to the control tower for this purpose, each with one of the massive wooden stools that provided seating in our accommodation, over terrain that was not yet completely levelled, where a few trees were still just about surviving, damaged by bomb splinters. The lessons could not, of course, achieve the goals set for our school year under “normal” conditions at home, especially since, with the increasingly frequent air raids, they had to be interrupted immediately at the pre-alarm, even during the day, before the sirens wailed outside, while we, with our stools on our hunched backs, strived at high speed towards our gun tower, rushed up one of the four huge spiral staircases to cover our 2-cm cannons and got them ready to fire.

However, we never got to fire them but, from our balcony, where the weapons were positioned, we were able to marvel at the first daylight raids by the USAF, which began on March 4th and 6th, 1944. March 1944, and how the throngs of bombers flew towards their targets completely unfazed by the dense black flak cloud of the constantly thundering 12.8 twin barrels of all three gun towers in the city, dropping glittering swarms of stick bombs and some high-explosive bombs and causing a huge mushroom cloud of fire and smoke to the north of us. Two or three hits, i.e., “kills”, were observed by others; the only success of the continuous thunderous fire visible from my post was a parachute sailing down with a black soldier on it, which landed exactly on the control tower to great hullabaloo. There, during the November attacks of 1943, a high-explosive bomb had destroyed a 2-cm single gun at night, but the soldiers and Luftwaffe helpers had, fortunately for them, been ordered inside a few minutes earlier. Their gun had completely disappeared, and the supervising teacher StR. W. then provided a dramatic description of this event to the school, as he had been sitting in his parlour almost directly below it and his steel screen, apparently not properly closed, had been torn open by the suction...

The big night raids by the British stopped in mid-February but, from then on, fast, light bombers, the “Mosquitos”, frequently haunted the sleeping capital of the Reich, and of course we had to go out every time to cover the guns, swearing quietly, and then idly watch the nocturnal spectacle high up in the Berlin sky. The numerous searchlights, which in a clear sky “caught” every single aircraft with great precision and then reached further and further to the next one, the colourful “Christmas trees” that were dropped first and were probably intended to simulate a large-scale attack that was about to begin, the enormous banging double barrels of the 12.8-cm guns above us, producing many glittering sparks around the silver glowing aircraft that were quickly passing by, which from below looked like those of our lighter on the gas cooker at home. Nevertheless, I never saw one shot down, and the bombers quickly disappeared each time after everyone had dropped their “apartment block cracker”, which came down somewhere with a terrible roar, followed by a huge explosion - once so close that we took cover behind the thick balcony parapet in fright.

We experienced the last daytime attack on Humboldthain tower on April 29th; and I, already with a bandaged foot in a clog, photographed the resulting fires in the south of Berlin which, however, raged quite far away. A week later, I was sent to the “precinct” in the Friedrichshain flak tower after an infected wound could not be healed by our medics. On the way, I was loudly and vehemently pitied by Berlin housewives as I limped from the S-Bahn station to the tower: “It’s a shame, now they’re destroying such young guys too...”

I then lay there, on the ground floor, for several weeks and experienced the heavy daytime attacks on the east of Berlin on May 7th, 8th and 19th in the safety of the bunker, with a phosphorus bomb burning directly under our steel screen, which was of course firmly closed during the attack, and numerous injured people dug out of the cellars being treated. At one point, our supervising teacher Prof. L. kindly visited me, and two friends also appeared at my bedside and told of their experiences during the last attacks. When my foot had healed to some extent, I was even granted a few days’ convalescent leave - at my request - by the friendly staff doctor.

We experienced July 20th, 1944, barely a kilometre away from Bendlerstrasse, when at noon a Luftwaffe helper was posted in the stairwell on each floor, armed with a carbine, without knowing who was to be shot at! The next morning, I had my leave pass for the long-awaited “home leave” (10 days + 2 travel days!) in my pocket and then learned, much to my dismay, that from then on, an absolute ban on leave had been ordered. It was only late at night, long since lying in our beds, that we heard for ourselves from a comrade’s radio what had happened, through Hitler’s guttural voice. I must confess that at that time I was furious with the assassins because they had spoiled my home leave...! But the very next morning, the holiday ban was lifted. I had to run from one to the other again to collect the necessary signatures for a new leave pass but, on July 22nd, I actually travelled home from Anhalter Bahnhof.

When I finally reported back from leave at Zoo flak tower (the battery had moved there at the beginning of May), the whole troop had gone out shooting in Dramburg in Pomerania. Hans K. celebrated his 16th birthday on the way there in a freight wagon at Stargard station and later told me how they had riddled airbags, balloons, and dummy tanks there with the new 3.7-cm gun and set the moor on fire with tracer bullets. I, on the other hand, still had a lot of free time in Berlin for a few days, running errands for a midshipman in the big city from time to time. I was amazed to see that a lot had remained intact, especially in the old city centre. On June 21st, 1944, from the Zoo tower, we watched this area go up in flames during a massive daylight raid, the tower of the cathedral burning with a green copper flame and the sun disappearing behind the clouds of smoke over the city. We stood idly by as usual.

Once, we almost got a shot off. As a flight dispatcher looking north, I suddenly saw several single-engine fighters coming from “direction 2” low over the houses during a daytime attack, yelled the alarm in accordance with regulations, and the comrades turned the guns in that direction. We could already hear the 3.7-cm of the Humboldthain and Friedrichshain flak towers firing and, while the first aircraft crashed downwards, creating a dark cloud of smoke there, we saw four USAF “Mustangs” pull steeply upwards, pursued by some dying 3.7-cm flak shells, but out of range of our own guns. The somewhat envious excitement about the shoot-down was great; when the telephone rang later, I had to get the ensign on the phone, who took a report with the remark “What a bummer” and then said to me: “That was a Focke-Wulf that went down there at Rosenthaler Platz, not a Mustang. But don’t tell anyone!” Apparently, that German fighter, pursued by the Mustangs, had tried to land on Tempelhofer Feld.

One week after the invasion, when Prof. L., gave us the essay topic: “On what do we base our hopes of victory?”, I sat distraught in front of the lined paper and, for the first time in my student existence, did not know what to write. I promptly received a C-minus for it (I was otherwise used to many As and at worst Bs for my essays), and Prof. L. had written in red in the margin: “And the wonder weapons?” I hadn’t mentioned them (the first V 1 didn’t fly to London until June 16th), so where were they then, these effective wonder weapons?

But as far as those “hopes of victory” were concerned, I experienced a final shock, so to speak, in August when I was on lift duty and, accompanied by a tremendous banging of heels, the “Reich Marshal” Göring appeared in the entrance. The lift operator said: “Come on, get lost, I’ll have to take Hermann up myself”, namely up to the VIP hospital but I looked for a few seconds into his lowered, gloomy face, a completely different face than the one on the balcony of the Reich Chancellery after the victorious French campaign, in view of the cheering masses in the summer of 1940, in that newsreel...

I left the lift alone and hurried up to our accommodation, where my comrades were playing cards, of course, and Helmut L. was bidding, and I said: “Do you know something? I’ve just seen Göring, with a face like this... We’ve lost the war!” Helmut S. said: “24 - 27 - pass” and then: “Well, if you’re going to say that now...”

Luftwaffe helper Hans K., who, for reasons he can no longer explain, was often on guard duty at the top of the guns, was met there by Luftwaffe General Bodenschatz in his pyjamas, his arms completely bandaged since the assassination attempt on July 20th, and the Minister of Nutrition Backe with a quince-yellow face, probably the result of severe hepatitis. They kindly asked the little Luftwaffe helper about his domestic and school circumstances. Of course, a Minister of Nutrition suffering from jaundice seemed somehow strange to him!

One experience as a lift boy hobnobbing with celebrity was rather embarrassing: the highly decorated fighter pilot Galland (who survived the war for a long time in South America and, according to my information, once solemnly married a girl from our hometown in the town hall) and an SS general with the Knight’s Cross entered the lift and demanded to be taken up to the military hospital, where air force general Bodenschatz was still recuperating.

While I was handling the crank, the famous Galland asked me - somewhat patronisingly, of course – “Well, my boy, surely you want to be a fighter pilot one day...” and I, completely honestly and addressing him correctly, answered briskly: “No, Inspector General, I’m staying with the FLAK!” He then turned his back on me, offended, but the SS general grinned all over his face. A few days before, I had actually volunteered for the Luftwaffe Flak as a reserve officer (almost all of us did so because of the shortened basic training period and in the hope of not being immediately burnt out later on). Impressed by the flak weapons, and because we had already been trained in two calibres at that time (later there were even four!!), I had decided to do so.

However, one day at the end of March or beginning of April 1945, I was summoned to the barracks at home, to the horror of my parents, where a friendly older girl told me that my application to the air force had unfortunately been rejected, but that I could now apply to the infantry, where officers were certainly needed... I could fill out the application right there! But I preferred to take the forms home and throw them away.

From our balcony, we watched the Berlin population living nearby and not yet bombed out stream into the tower entrance every time the alarm sounded; this began when the air situation reports on the radio announced that a “bomber group north of Braunschweig heading east” was on its way, and the sirens had not even announced the “pre-alarm”. The people seeking shelter then crowded the ground floor and the large spiral staircases in the corner towers. It is said that there were sometimes several thousand of them! At the last moment, when the heavy flak on the western edge of the city had already started firing, we saw some senior officers from the “Bendler Block”, some with red piping on their trousers, rush into the tower.

Of the three Berlin towers, the Zoo flak tower was the most “distinguished”, so to speak, not only because of the celebrity hospital on one floor, but also because it was equipped with a cinema hall, on the stage of which we were even once allowed to experience a military service event - although the dancers from the famous Dresden “Palucca School” were essentially appraised by the flak soldiers according to their proportions. There was also a grand piano on which my friend Otto M. occasionally - the door to the stage was unlocked - played popular hits of the time, such as “Kauf Dir einen bunten Luftballon...” or “In der Nacht ist der Mensch nicht gern alleine...”, and, very delicately twanged, Horst Wessel’s hurdy-gurdy melody “Die Fahne hoch...”. Even then I had wondered, half unwittingly, about the sadly falling tone sequences of this party song, which had nothing at all stirring or “heroic” about it. In fact, it is said to have been a moritata melody simply converted into a second national anthem! The Italian fascist anthem was a different matter, played briskly and brashly, to which, however, we added (in 1944!) the text: “Wiiir sind tapfre Italieeener, uuunser Land wird immer kleeener...” (We are brave Italians, our country is getting smaller and smaller...).

In September, the class of 1927 left us; they were drafted for “fatigue duty”. But we were sent with all our ranks to Rüdersdorf in the east of Berlin to an 8.8-cm battery. The barracks and the lavatories were unusually primitive, but the nearest fields were very close, and I can still see the three of us, Otto, Christian and me, roaming around there in the evening, taking some of a pile of carrots with us, watching the farmers drive off with the turnips, when a wagon got stuck and finally a log broke, as Christian compassionately and expertly observed, and it became clear to me that he, coming from the village, had suffered even more than I (who had already been separated from my garden for nine months) from the lack of countryside and the absence of the smell of stable manure and freshly ploughed earth...

The landscape then remained constant until the end. In Rüdersdorf, the training on the 8.8-cm, as it turned out only a week later, had been superfluous, although it was of course something new for a technically interested student like me, especially since I did not have to play loading gunner like my friend Otto M., which was quite a slog with the “88”, especially when firing almost vertically.

Source: www.seniorennet-hamburg.de – ©2001 Dr Wolfgang Waldhauer

We thank Dr Waldhauer for permission to reproduce his memories here.

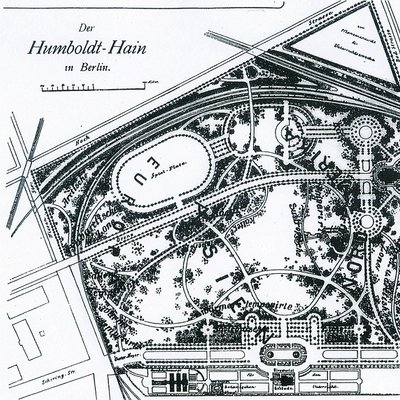

Volkspark Humboldthain

During the crazy growth years in Berlin, a veritable building anarchy prevailed outside the city limits; nothing was regulated or organised, well-funded city dwellers had just discovered the construction of multi-storey “family homes” as a cash cow. The building regulations of 1853 barely determined the size of backyards and the height of façades. The emerging industry, however, demanded a minimum of infrastructure, and building councillor James Hobrecht was commissioned shortly afterwards to draw up a development plan for the entire surrounding area of what was then the city boundary (roughly Torstrasse).

Hobrecht’s basic idea was not to build a large, central city where everything is oriented exclusively towards the centre, but to create individual neighbourhoods, which we today call “Kieze”. Small streets and squares were to define life here and, in each of these neighbourhoods, a “Karree” - a small park spread over one or two blocks - was to be created where the population could find recreation. In addition to Hobrecht’s planning, it was decided by the city to create a large Volkspark in each district. The largest parks were planned for Friedrichshain, Humboldthain, and Kreuzberg.

Hobrecht’s vision of a social urban structure envisaged that the large industrial complexes would be located outside the city, or at least in their own blocks. Regarding the recreational areas, the development plan states: “The public squares are to be distributed as evenly as possible; they are either located between the streets, like the building quarters, or where main streets meet, and are most usable when they lie to the side of a main street. As far as their shape is concerned, the rectangular ones appear to be the most usable (...) The squares must serve public facilities, for public buildings, namely for churches, which must be set back from traffic, and furthermore for playgrounds, promenades, and gardens.”

Planning and design

In 1865, the Berlin city council decided to acquire the land next to the slaughterhouse for a Volkspark of approximately 29 hectares. The planning and preparation by the gardens director Gustav Meyer took four years, so that construction work could not begin until late summer 1869. The ground-breaking ceremony for the Volkspark, which was completed in 1876, took place on September 14th, 1869, the 100th birthday of Alexander von Humboldt. The public festival to mark the laying of the foundation stone is considered the first public appearance of the Berlin Social Democrats after the founding of the Social Democratic Workers Party (SDAP) in Eisenach the previous month.

On the one hand, the park was intended for the leisure and recreation of the surrounding population but, at the same time, it was also to serve their further education. Thus, in addition to the toboggan run and the playgrounds, there were numerous exotic and rare plants that were arranged according to their regions of origin. Small signs pointed out the name and origin. The 340,000 marks earmarked for this amenity also included the construction of an elaborate irrigation system, which alone took several years to build.

The park as we know it today looked completely different back then. Above all, it differed along today’s Gustav-Meyer-Allee as well as the actual grove. Opposite Ramlerstrasse, there was a square on which the Church of the Ascension stood, a monumental brick building built according to plans by the Royal Building Council August Orth from 1890 to 1893 and very badly damaged in the Second World War during the final battles for the city in late April/early May 1945. From the west side of the square, where Wiesenstrasse still runs today, Grenzstrasse ran right through the park to the church and Brunnenstrasse. The open-air swimming pool that we see today did not exist at that time, of course.

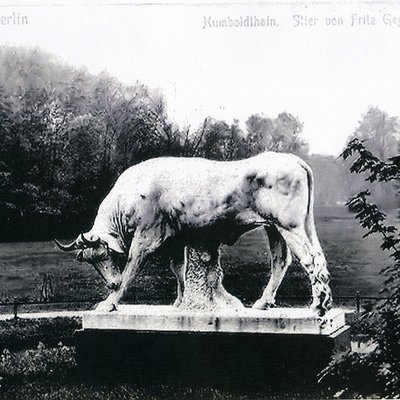

The cattle and slaughterhouse adjoined to the south. When this was closed and the AEG built its halls there, part of Humboldthain was sacrificed to the factory grounds. As an extension of Rügener Strasse, a previously wide park promenade was turned into Gustav-Meyer-Allee, originally with a planted central strip and a small square in the middle of the street. In 1888/89, several boulders were erected on top of the grove, as well as an inscription plate referring to Alexander von Humboldt. The park had been named in his honour; he had died ten years before the construction of the park began. Next to it, an artificial spring was built, which fed a small pond containing foreign fish. In 1901, a rose garden was created opposite the director’s building on the southern edge of the park and, in 1902, the sculpture “Der Stier” (The Bull) by Ernst Moritz Geyger was erected in the park. But probably the most important monument was created in 1927. The sculpture “Diana with Greyhounds” (also called “Hunting Nymph”) by Walter Schott, however, did not arrive at its present location in the rose garden until 1987. It was donated to the Wedding district by AEG in 1953 but was located elsewhere.

The Second World War and Post-War Period

During the Second World War, Volkspark Humboldthain was “misappropriated” by the Nazis for their purposes. First, two semi-subterranean so-called flat bunkers were built along Brunnenstrasse as “mother and child bunkers”.

From October 1941 to April 1942, two gigantic high-rise bunkers were built with the help of French forced labourers and Soviet prisoners of war, which completely destroyed the park. One was the tower for the anti-aircraft guns at the northern edge of the park, the other was the anti-aircraft control tower on Gustav-Meyer-Allee at the southern edge of the Volkspark.

After the war and the two cold winters that followed, Humboldthain was effectively utterly destroyed. All the trees had been cut down for heating; only the bunkers were still standing. The first to be blown up were the mother and child bunkers in 1947. Then, after several partly unsuccessful blasting attempts, French engineers also destroyed the two flak towers. The bunker ruins were subsequently largely filled in with the approximately 1.3 million cubic metres of rubble that were brought from the bombed-out surroundings by rubble trains and horse-drawn carts. The burnt-out ruins of the Church of the Ascension also disappeared in the masses of rubble, and the last thing to be blown up was the once 72-metre-high church tower on July 14th, 1949.

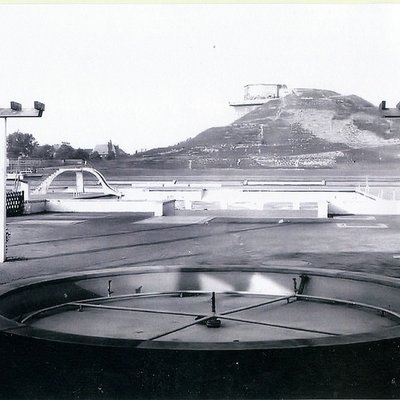

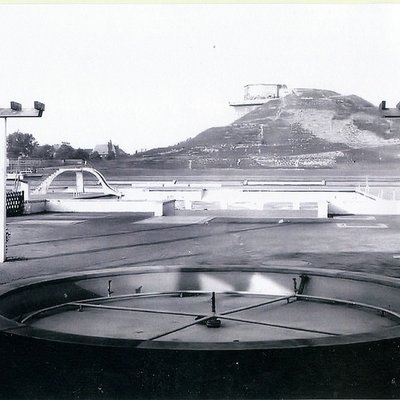

From 1950 onwards, a completely redesigned park was created by Günther Rieck, partly financed with money from the Marshall Plan. A toboggan run was built above the smaller flak bunker, the former control tower, while the mountain of rubble from the large bunker was landscaped and the “Memorial to German Unity”, a metal sculpture from 1967 by the artist Arnold Schatz, was erected on its “summit”. On the site of the former Church of the Ascension on Brunnenstrasse, there is now a rose garden that is also well worth seeing which was created in the post-war period.

And while the people of Wedding look for their picnic spot in the grass and the children amuse themselves in the summer pool or the educationally supervised playground, today you can walk up to the 85-metre-high platform on the large bunker hill. From there, you have a great view in all directions.

Before this was possible, however, the bunker had to be extensively renovated. For decades, it had been left to its own devices after the rubble had been removed and, for good reason, it was forbidden to enter it. There were still holes and crevices, partly former window and door openings, partly openings created by the blasts, which allowed access to the ruinous interior. The fact that this was a life-threatening undertaking did not deter adventurous youths and adults from entering.

There were repeated accidents, one of which ended fatally in the spring of 1982, and so it was decided to either demolish the bunker completely or secure it. It took years before the idea of demolition was rejected for cost reasons and the necessary work began in 1988. Openings were sealed, the façade was secured with shotcrete, and the stairs and the former lower combat platform were repaired. A 3-metre-high fence was then erected on the parapet and the former upper gun platform, which had meanwhile been converted into a viewing platform.

On July 10th, 1990, the “Humboldthöhe” (Humboldt Heights) was ceremoniously opened to the public. Of course, the name had been chosen almost 40 years earlier when, in 1952, a naming competition was initiated by the Wedding district office. Hundreds of entries resulted and so, today, the hill could also be called “Plumpenpickel” (Hulking Pimple), “Bombast” or “Großer Busen” (Big Boobs). Fortunately, it was suggestion No. 777, that of a Mr Otto Lengner from Hermsdorf, that managed to garner the most votes (159).

There is also a new Church of the Ascension, but now on Gustav-Meyer-Allee, just a few steps away from Brunnenstrasse. After its merger with the Friedensgemeinde (peace community), it is now called “Kirche am Humboldthain”.

Extracts from www.brunnenstrasse.de, www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de und www.luise-berlin.de

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Landesarchiv Berlin

© Landesarchiv Berlin

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Archiv Berliner Unterwelten e.V.

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

© Holger Happel

instagram takipçi satın al - instagram takipçi satın al mobil ödeme - takipçi satın al

bahis siteleri - deneme bonusu - casino siteleri

bahis siteleri - kaçak bahis - canlı bahis